This article appeared

on the Op-ed page of the Wall Street Journal December 14, 1981.

"The evidence suggests that each percentage

point drop in the inflation rate should send about $100 billion of the

tangible assets people hold back into the financial markets as increased

credit supplies."

It is now said that the federal deficit for fiscal 1982 will be roughly

$100 billion. This has sparked a furious debate between Wall Streeters,

who say such large government borrowing must push interest rates

higher, and supply-siders, who believe tax cut-induced increases in household

savings will more than offset rising government borrowing needs, and hence

must push interest rates power.

This fight represents a low of wasted ink. It reminds me of the scene

from the movie in which Frankie Avalon and Annette Funicello are frantically

trying to brush those pesky ants from their picnic blanket, when a creature

emerges from the surf in the background. Remember how we screamed ourselves

hoarse trying to warn them? "Look out, Frankie!" "Turn

around, Annette!" They just wouldn’t listen.

In my view the obsession with both Wall Streeters and supply-siders

with analyzing credit flows has led both to forget who the real

star is in the interest rate story.

Major changes in U.S. interest rates are usually caused by changes

in the way the public wants to hold its net worth. The point of this

article is that the drop in inflation in the last 18 months is forcing

households to restructure their wealth in a way that will force reductions

in interest rates n 1982, no matter what the level of savings or budget

deficits in the next year.

Flow-of-Funds Focus on Savings

Both sides of the debate use a flow-of-funds framework to forecast

interest rates. This framework views a financial market as a kind of

farmers’ market, where households bring their savings (credit supplies)

and governments and corporations bring their borrowing needs (credit

demands). Interest rates are the price that equates credit demands and

credit supplies. This is the source of the current fixation on deficits

and savings.

Wall Streeters fear that mega-deficits will piggyback the growing calendar

of corporate debt issues to explode credit demands. Savings won’t

be able to increase fast enough to meet these needs. After a brief dip,

due to the recession, short-term interest rates will climb to new highs

by late 1982. Long-term rates won’t budge from current levels because

institutional portfolio managers translate large budget deficits into

fear over rising future inflation.

Supply-siders believe the tax cut will increase the after-tax real

rate of return on investment income, inducing households to increase

savings. These increased savings, they argue, will provide more than

enough credit to satisfy government and corporate appetites for funds,

letting interest rates fall during 1982. And savings will continue to

grow, so exploding interest rates shouldn’t be a big problem through

the ’84 elections.

The debate, then, has largely degenerated into a doctrinal dispute

over the degree to which private savings will be stimulated by Mr. Reagan’s

tax cuts. To both groups, the key question is by how much and how quickly

personal savings will respond to changes in the after-tax real rate

of return.

Forced to choose between the Wall Street and supply-side views, I would

go with the supply-siders. There is ample evidence that households do

respond to change in relative prices – witness the phenomenal growth

of the money market funds (from $11 billion in 1978 to $150 billion

in 1981). Moreover the evidence, though not conclusive, bears some resemblance

to the supply-side view. Since Mr. Reagan took office, real after-tax

rates of return have stepped up households’ savings (i.e.,

they have stopped spending money). Since mid-August, interest rates

have fallen sharply.

In adopting the flow-of-funds framework of interest rate forecasting,

both sides neglect the fact that, in addition to owning stocks, bonds,

bank accounts, money market certificates and other financial assets,

households also owns condominiums, land, used cars, gold and countless

other tangible assets. This stock of existing goods, or tangible

assets, has been produced and stockpiled over many years, and in a real

sense represents the nation’s collected real wealth.

The stock of tangible assets in the U.S. is enormous. At today’s

prices the total stock of houses, cars, collectibles and other tangibles

is worth about $7 trillion. That’s more than twice the total value

of the goods and services the U.S. economy will produce this year.

I believe that failing to recognize the existence of the stocks

of tangible assets renders flow-of-funds analysis almost worthless

for forecasting interest rates.

To private investors, tangible assets are substitutes, or alternatives,

to financial assets. They ask: Should I buy a condominium or should

I put my money into a T-bill account? Should I sell some of y shares

of stocks to buy gold coins?

To consumers, tangible assets are substitutes for buying currently

produced goods and services. Should I buy a new car or is my current

car good enough for one more year? Since the amounts in question are

so huge -- $7 trillion – even a moderate sift in the way households

want to hold assets can have a huge effect on both credit markets and

durable goods sales.

The key to understanding the influence of tangible assets on interest

rates is the concept of "asset market equilibrium." An individual

is free to hold his wealth in any combination of assets he chooses.

One person with a net worth of $40,000, for example, may choose to hold

$20,000 in gold coins and $20,000 in currency. Another person, with

the same net worth, may choose to hold a $100,000 house, financed with

an $80,000 mortgage loan, $12,000 in furniture, automobile and personal

effects, and an $8,000 savings account.

Asset market equilibrium describes the state in which each and every

asset holder in the economy has gone through his own process of portfolio

selection, and now is holding the combination of assets which, at current

market prices, he finds most desirable.

What happens if people desire more condominiums than exist? Individuals

bidding for that scarce supply would drive the price higher, and the

attempted sale of bonds or other securities to fund the condo purchases

would tend to force securities prices down. These price changes tend

to lower the yield on condos as an investment and raise the yield on

bonds, causing people to reconsider their initial choices. Ultimately,

both condo and security prices settle at levels which, again, make people

content to hold the existing stock of assets.

This is not a new idea. James Tobin just received the Nobel Prize in

economics for developing the notion of portfolio balance. Mr. Tobin’s

idea was that the prices (interest rates) of financial assets will go

to whatever level will make investors just content to hold the available

stock of those assets. All we have done is to add tangible assets –

land and so forth – to the portfolio management problem faced by

every household.

This addition radically changes the nature of financial analysis and

interest rate forecasting. It breaks the link between savings and credit

supplies that plays such an important role in the flow-of-funds framework.

A household that owns at least some tangible assets can supply credit

in two distinct ways: 1) by increasing savings, i.e., buying securities,

with money out of its current income, or 2) by selling some portion

of its tangible asset holdings to buy bonds, stocks or T-bills. The

results are the same, increased credit supplies and lower interest rates.

Thus, a general increase in the public’s desire to hold financial

assets – a desire to exchange tangible assets for financial assets

– should be seen as an increase in credit supplies. Since the public’s

holdings of both tangible assets ($7 trillion) and financial assets

($7.3 trillion) are extremely large, a relatively minor change in their

desired stocks of assets can overwhelm savings and budget deficits in

its effect on interest rates.

In short, we should treat households as managers of portfolios of real

and financial assets. Their decisions about which assets to hold and

in what proportions to hold them will be based on the same criteria

as the decisions of the professional money managers; namely, expected

yield comparisons. The choice between tangible and financial assets

forces households to compare the expected yields on financial assets

-- roughly, interest rates – with the expected yield on owning

tangible assets. Often, the yield in tangible assets will include both

a stream of services – e.g., you get to live in your house –

as well as the potential for any increase in resale value of the asset

– because housing prices go up – during the time it’s

held. At this stage inflation enters the picture for determining interest

rates.

A sharp increase in inflation, for example, means an increase in the

yield on real assets relative to paper assets. Like any portfolio manager,

the people who run households are attracted to the high return on real

assets and try to increase their holdings of houses and durable goods,

using money obtained by selling securities. The result, upward pressure

on prices for houses and durable goods, and downward pressure on prices

for bonds and other securities, i.e., rising interest rates.

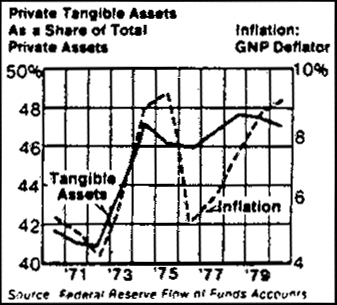

The following graph shows how people changed their holdings of tangible

assets as the inflation rate varied during the 1970’s.

At the end of 1972, for example, the inflation rate was below 5%, and

about 41% of private sector assets were tangible assets: this implies

that financial assets made up about 59% of the assets of households

and businesses.

Within two years the inflation rate rose to nearly 10%. This increased

the yield of tangible assets relative to financial assets, so people

tried to cash in their stocks, bonds and bank accounts for money they

used to buy houses, gold and antiques. The result: a 6% shift of private

assets out of the financial markets and into tangible assets. That 6%,

roughly a $400 billion shift, caused a major drying-up of credit supplies.

Is it any wonder that interest rates soared in 1974? Rising interest

rates and rising prices for gold and real estate are not simply related

events; they reflect the same shift in household decisions about the

safest way to hold onto their accumulated wealth. And the thing that

sets off these decisions is inflation.

Turn the above analysis on its head and you’ll have the right

analysis for 1982. In the last 18 months, U.S. inflation has slowed

dramatically, undermining tangible asset yields. Residential real estate

prices across the country are falling. At the same time, T-bill rates

and other yields on financial assets have been at historic peaks. This

has opened a gap between paper and real asset yields that, to some of

the more aggressive inflation hedgers, looks like the Grand Canyon.

As some households make the inevitable shift away from tangibles and

back into higher-yielding paper, credit supplies will grow and interest

rates must fall.

We expect 1982 inflation to fall to 6%. This means a continued lackluster

performance for real asset yields. I am not saying that everyone who

is reading this will rush out and sell his house or buy a bond, or that

everyone in the U.S. will begin to think like a currency arbitrageur.

But the available evidence suggests that each percentage point drop

in the inflation rate should send about $100 billion of the tangible

assets that people hold back into the financial markets as increased

credit supplies.

Since the inflation rate for 1982 (6%) should be about four percentage

points lower than the 1981 figure, this suggests we’ll see an increase

in credit supplies of $400 to $500 billion for 1982 without counting

on a nickel of increased savings. If the administration’s tax cut

stimulates private savings by a significant amount, the case for lower

interest rates is stronger still. To my knowledge, no one has yet announced

that the deficit will hit one-half trillion dollars for 1982. If it

does not, interest rates must fall.

Postscript, April 27, 2000

To my delight, this article stimulated a spirited debate in the pages

of the Wall Street Journal. Art Laffer and Gary Shilling –

both very good friends today – wrote articles explaining why I

was wrong. I was invited to defend myself on the Op-ed page. The debate

continued in the WSJ, Barron’s, Forbes, Fortune,

the New York Times and the Financial Times during the

first half of the 1980’s. It was a career-building event

Irving Kristol started the whole thing in September 1981 at the bar—where

else would one think so expansively – of the New York Athletic

Club. I described the tangible asset analysis, which I had used to forecast

interest rates over the previous four years, to Irving on a bar napkin.

I offered it as a counter argument to the then-popular views of Dr.

Doom and Mr. Gloom that interest rates would head ever higher. Irving

said he thought it was an important idea that should be published in

the Wall Street Journal. He called Bob Bartley the same day. I owe both

of them my a large thank you. Twenty years later, Irving Kristol and

Bob Bartley, along with Charley Parker, the man who introduced me to

Irving and has been my best friend ever since, are the most intellectually

curious and intellectually honest men I have ever known.

Years later, Bob Bartley wrote a wonderful book called The Seven at

Years which reviewed the events surrounding the major policy decisions

of the 1980’s. In the book, Bob referred to this analysis with

very kind words.

As it turned out, the idea was a pretty good one too. Inflation has

declined from more than 10% to about 2% in most industrialized countries.

Households today hold less than 30% of their wealth in the form of tangible

assets, compared with nearly 50% in 1981. Interest rates have fallen

from above 15% to below 6%. Bond and equity holders have made 20 times

their money over the period. And if flow-of-funds analysis in forecasting

interest rates is dead today, I am happy to have played a role in killing

it.

Does the idea still work? For 20 years it provided a true North to

investors as the relentless disinflation drove rates lower and lower.

In the late 1990’s, the story got a new pair of legs from the technology

boom, which further undermined inflation. Today, although low inflation

still rules, the adjustments I described in this article—the forces

which drive interest rates lower -- are now complete. Other factors

have become more important. But don’t put the idea away. The next

time inflation heads higher, or lower, it will still help us understand

interest rates.

|