|

A dividend tax cut would

raise the after-tax return on dividend paying assets above that

on all other assets. The resulting thermal disequilibrium would

lead investors to rebalance portfolios, driving dividend paying

asset prices up relative to other assets. The Intrinsic Value of

the S&P 900 would rise by 5.1% at a 20% tax rate, and 8.5% at

a 0% tax rate, increasing net worth by $481 billion, or $799 billion,

respectively. Differential effects vary widely by sector. There

are huge potential further gains for companies that increase payout

ratios and reduce debt.

The Bush dividend tax cut will be the biggest event to hit the asset

markets since the 1981 Reagan tax cuts. It will have a huge impact on

asset prices, interest rates, growth, and the dollar. It will create

a host of opportunities for investors to make money. It will also create

a wave of restructuring, recapitalization, and acquisition events among

US companies.

Conceptually, a dividend tax cut would impact stock prices in two

phases. Initially, it would work by raising the after-tax return on

dividend paying assets above that on all other assets. The resulting

thermal disequilibrium, characterized by an unsustainable gap between

after-tax returns, would lead investors to individually attempt to rebalance

their portfolios, selling non dividend paying assets to buy dividend

paying assets.

Collectively, these attempts would drive the prices of dividend paying

assets up relative to all other assets, which would reduce the after-tax

return gap until returns were driven back in line. These price changes

would increase the market value of equities, as well as the net worth

of investors.

A reduction of the dividend tax rate from 38.6% to 20%, for example,

would increase the Intrinsic Value of the S&P 900 by 5.1% and increase

investors’ net worth by $481 billion.

A reduction of the dividend tax rate from 38.6% to 0% would increase

the Intrinsic Value of the S&P 900 by 8.5% and increase investors’

net worth by $799 billion.

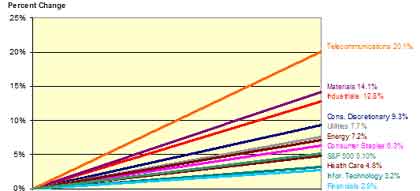

Effects vary widely by sector, as shown below in Chart 1; the biggest

effects will occur in sectors with high dividend payout ratios and no

debt. In the Telecommunications sector, for example, the reduction to

a 20% dividend tax rate would increase equity value by 20.1%; the reduction

to a 0% dividend tax rate would increase equity value by 33.4%.

Chart 1

Stock Price Impact of a 20% Dividend Tax Rate

These initial effects will be followed by a second round of potentially

larger stock price increases as managers alter company strategies to

take advantage of the new tax regime. One-time special dividends to

distribute excess cash, increased payout ratios, and issuing new shares

to reduce debt will all increase value. These opportunities, which are

concentrated in sectors with low payout ratios, like Information Technology,

could be huge. Raising the dividend payout ratio in the Information

Technology sector to 100%, for example, would increase equity values

by 42.1% in the case of a 0% dividend tax rate.

Dividends are currently taxed twice, once at the corporate level,

then again at the investor level, which makes it hard to get a dollar

of profit into an investor’s pocket. Consider, as an illustration,

XYZ Corporation. At current tax rates XYZ has to earn $2.51 in pretax

profits to put $1.00 of dividends in its shareholders’ pockets.

Out of the $2.51 of pretax profits it pays $0.88 (35% of pretax profits)

in corporate income taxes to the IRS, leaving $1.63 in after-tax profits.

If it pays that $1.63 to investors as a dividend, the investor who receives

the dividend pays an additional $0.63 (38.6% of dividend income at the

top marginal rate) to the IRS, leaving exactly $1.00 in his pocket.

Double taxation makes dividends an extremely leaky and inefficient bucket

for carrying profits from the corporation to the investor. Overall,

$1.51 (60%) of XYZ’s original $2.51 has gone to pay taxes; only

$1.00 (40%) found its way to the investor. In comparison, both interest

payments and capital gains are more efficient channels for paying profits

to investors. It would cost XYZ only $1.63 in interest payments to put

a dollar of after-tax income in investors’ pockets, since interest

is deducted as an expense at the corporate level. Better still, XYZ

could put the same after-tax dollar in investors’ pockets by delivering

only $1.25 in the form of capital gains—tax free to the corporation;

20% tax rate to the individual—by reinvesting profits to generate

growth or by “investing” its after-tax profits in stock

buybacks.

Not surprisingly, corporate managers have figured this out; paying dividends

has gone out of style. Only 20.8% of public companies paid dividends

in 1999, down from 66.5% as recently as 1978. Those that do pay dividends

are paying out a lower share of profits or using stock buybacks in their

place.

Double-taxation of dividend income has given rise to serious inefficiencies

in capital markets. It has diverted capital away from business ventures

that produce reliable, large, and growing free cash flow streams for

their owners in favor of companies that produce no profit but offer

a hope of future capital gain. This distortion of managerial incentives

was a material contributor to the excesses of the stock market boom

in the late 1990s and to the severity of the subsequent correction.

It also created the presumption in the minds of many managers that they

should avoid paying profits to investors, which contributed to the governance

scandals that were exposed by declining equity values in the past few

years.

Cutting the dividend tax rate at the investor level to zero would promote

more efficient use of capital among competing uses by removing the existing

distortion among the after-tax returns that guide investor behavior.

Here’s how it would work.

The way to understand the dividend tax cut is to focus on the economy’s

capital accounts by analyzing the effects of changes in the dividend

tax rate on relative asset demands, therefore on asset prices and investment

spending. This framework has its roots in the laws of thermodynamics—the

most trusted principle in physics, chemistry, and biology.

Here’s how it will work. Start with the example of a zero-growth

company XYZ, discussed above, that has no debt and pays out 100% of

its after-tax profits as dividends. Last year, the company paid shareholders

a dividend of $1.63 per share. Shareholders paid 38.6% (their marginal

income tax rate) of the dividend, or $0.63, to the IRS and put the remaining

$1.00 in their pockets. XYZ’s stock price is $20 per share. Shareholders

earned a 5% after-tax return on their investment—$1.00/$20.00—which

is exactly equal to the after-tax return on all other assets.

In thermodynamics, if you put a hot object and a cold object into contact,

heat will flow from the hot to the cold object until they reach thermal

equilibrium where there is no temperature difference. You can try this

yourself by placing a steaming hot dog and an icy cold can of soda into

your child’s lunch pail in the morning and ask them to report

what they find when they open it to eat lunch. (Your child may learn

some physics. Even better, they may start making their own lunch.)

If you put two objects together that are the same temperature, however,

nothing will happen. Physicists call this situation thermal equilibrium.

This principle works in asset markets just as well as in lunch pails;

only in economics we call it arbitrage and we refer to thermal equilibrium

as portfolio balance. Unlike heat, however, money runs uphill, from

low after-tax return to high after-tax return investments. Just like

in physics, asset markets reach thermal equilibrium when after-tax returns

are equal.

Our XYZ company example, above, is in thermal equilibrium because all

assets have the same 5% after-tax return. There is no opportunity for

investors to improve their net worth position by trading one asset for

another. Regardless of what they own, they will earn 5% after-tax.

The dividend tax cut changes all that. Assume the government passes

a law that makes XYZ dividends tax-free. (A good lobbyist will do that.)

The company still pays the same dividend to the investor, but now the

investor gets to pocket the entire $1.63.

Now the investor earns $1.63/20.00 = 8.15% on his investment after taxes.

This is far better than the 5% investors are earning on other investments.

This metaphorical temperature differential means that asset markets

are no longer in thermal equilibrium. An investor can improve his position

be selling one of his 5% assets and using the proceeds to buy XYZ stock.

As all investors try to do so—they all have the same information—they

will run into a traffic jam. They will all try to sell 5% assets to

people who are trying to do the same thing, and will all try to buy

XYZ stock from people who are also trying to buy XYZ shares. In this

situation, we know one thing for sure; the price of XYZ shares will

go up.

How much? If the market capitalization of XYZ is small compared with

the market, so we can ignore the effects on other asset prices, the

price of XYZ will rise until after tax returns are again equal and thermal

equilibrium has been reestablished. This will happen when the price

of XYZ has risen to $32.60, at which price its owners will earn an after-tax

return of $1.63/$32.60 = 5% on their capital.

Where did the extra value come from? It is the present value of the

cash flow stream that has been diverted from the IRS to investors.

Cutting the dividend tax rate from 38.6% to zero has increased the Intrinsic

Value of XYZ stock from $20 to $32.60, an increase of 63%, which equals

the ratio of (1 – old tax rate) and (1 – new tax rate).

Analytically, we can describe this as a decline in XYZ’s cost

of equity capital, the return it must pay investors to remain competitive

with other uses for their capital. A decline in the cost of capital

increases equity values as a multiple of current after-tax profits.

The mechanism through which a reduction in the dividend tax rate from

the current maximum rate of 38.6% to 20% increases equity values is

shown in Table 1. The logic applies in exactly the same way to the case

of reducing the dividend tax rate to 0%, which is shown in Table 2.

Table 1 shows that a reduction in the tax rate on dividend income from

the current maximum rate of 38.6% to 20% would reduce the cost of equity

capital—the return a company must pay investors to attract equity

capital—for the companies represented in the S&P 900 by 90

basis points (0.9%), from 7.2% today to 6.3%. The reduction in the cost

of equity capital varies from 200 basis points for Telecommunications

companies to 20 basis points for Information Technology companies, since

the former pay out essentially all earnings as dividends while the latter

pay essentially no dividends. (I have used data on payout ratios for

2001, the last full year of data available from Compustat, to make the

calculations. In a rigorous valuation we would use, instead, estimates

of expected payout ratios over the life of the investment, which would

change the reported numbers in Table 1 and Table 2 somewhat.)

Lower cost of equity translates into lower cost of overall capital to

the extent a company’s capital structure is made up of equity,

rather than debt. (The Equity Capital Ratio data measures equity capital

(including both common and preferred equity) as a percent of total capital.

The decrease in cost of capital varies from 10 basis points for the

Information Technology sector to 100 basis points for the Telecommunications

sector, and equals 20 basis points for the broad market as represented

by the S&P 900.

A lower cost of capital increases the Intrinsic Value of a company’s

equity—the present value of future free cash flow less debt—by

reducing the discount rate used to estimate present values. As in the

case of bonds and real estate securities, the impact of a 100 basis

point reduction in cost of capital on Intrinsic Value will depend on

the shape of the expected future cash flow stream.

The Intrinsic Values of companies with front-loaded cash flow streams—those

for which the bulk of free cash flow occurs in the early years—would

be relatively insensitive to changes in the cost of capital. The technical

term for this is short duration, the time-weighted average maturity

of future cash flows. Those with back-loaded cash flow streams—high-growth

companies with negative cash flow in the early years—will be strongly

impacted by a reduction in the cost of capital. These are securities

with long durations.

Our estimates of the sensitivity of Intrinsic Value per 100 basis point

reductions in the cost of capital—21.2% for the S&P 900—is

shown in Table 1 for the overall market as well as its ten component

sectors. The column labeled Stock Price Impact shows estimates of the

impact of the dividend tax cut on the Intrinsic Value of the S&P

900 and its component sectors, taking all these factors into account.

Although overall stock prices should increase by just over 5%, the sectoral

impacts vary widely, from roughly 3%, for the Information Technology

and Technology sectors, to 20% for the Telecommunications sector.

These stock price increases will increase market capitalization and

investors’ net worth by $481 billion, with increases concentrated

in Industrials ($135B), Consumer Discretionary ($121B), Telecommunications

($79B), and Health Care ($65B).

This is only the beginning. Astute managers will soon learn that companies

that take advantage of the new, lower, tax rates will have lower capital

costs and become tougher competitors than others. Over time, they will

adapt their business practices to the new tax regime. The irony is that

the sectors, industries, and companies that will initially benefit most

from the lower dividend tax rate will have the least flexibility to

improve their value, while those that initially benefit the least have

the most to gain by changing behavior.

Many technology companies, for example, like Microsoft, have strong

cash profits and large cash balances, but pay no dividend. They will

have enormous latitude to increase their share prices by introducing

a dividend and paying large special dividends out of current cash balances.

Other companies that are principally debt-financed will benefit very

little initially, but have broad scope to increase value by selling

shares to reduce debt.

Shareholders will exert pressure on managers to increase dividend

payouts and deleverage their businesses. Managers who own stock or stock

options will gladly agree to do so. They will increase payout ratios

out of current profits and sell new stock to finance growth. And, they

will sell new stock to repay debt. Both will increase stock prices.

The upward limit of the resulting rise in stock prices ranges between

50% and 60% for different sectors. This could add 5% or more per year

to total returns for several years as companies adjusted to new tax

rates.

Preferred stocks, with high dividend yields, 100% payout ratios, and

implicit 100% equity financing, represent the most efficient way to

place a bet on the initial gains on dividend paying stocks. Straight

preferred stock could take on many of the characteristics of debt. Convertible

preferred stock issued by companies with low common stock payout ratios

(therefore, big upside from strategy change) are also attractive.

Common stock of companies or industries with big dividend payout ratios

(Verizon, SBC, BMY, IDU) are also attractive ways to benefit from the

initial price increase. The subsequent gains will accrue to companies

or industries with flexibility to increase payout rates, pay meaningful

special dividends, or refinance capital structure (MSFT, CSCO, INTC,

and SUNW).

Watch out for a head fake with Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs)

and Master Limited Partnerships (MLPs), and other securities with high

dividend yields which could be singled out for exclusion from the benefits

of the tax cut. In many cases they already have special tax status which

allows them to avoid double taxation, and are treated as pass-through

vehicles, similar to S-Corporations. If they get the lower tax rate

they will be wonderful investments. It they are singled-out for exclusion,

however, income-seeking investors will sell these assets to buy other

securities.

Treasury bonds, along with other fixed-income securities, are clear

losers. In the past year, investors have parked tons of money in Treasuries

and bond funds waiting for a better day. If the dividend tax cut ushers

in that better day, as I believe it will, bond yields will rise and

bond prices will fall substantially.

Hard assets that pay no dividends, such as land, commodities, and precious

metals will be affected in a similar way as investors shift from hard

assets, which pay no dividends, to dividend paying securities. Because

of this, the dividend tax cut should be viewed as at least a mild deflationary

impulse on goods prices and inflation rates. I will analyze the impact

of these changes on growth, investment, inflation, interest rates, and

the dollar in a separate paper.

|