I

feel like the snail that was mugged by a gang of turtles. When the police

asked if he could describe his attackers, the snail said, "I don't

know, it all happened so fast."

My day job is in the snail world of leveraged buyouts. I buy controlling

interests in midsized private companies and try to make them grow. We

always buy on margin. I won't know if an investment is successful until

I sell it three to five years later. Volatility means nothing -- there

is no price until the exit. The daytraders of the LBO world are "flippers,"

guys who sell companies in only 12 to 18 months.

I told

you I was a snail.

Bubbles,

Large and Small

In the past 30 years I've seen a lot of bubbles. My first was the 1974

oil embargo, when crude prices first jumped above $2 per barrel. At

the peak, my wheeler-dealer cousin Tony bought several 1,000-gallon

oil storage tanks, rented an empty lot and filled them with gasoline

so he could make a killing when prices jumped again. He probably still

has them.

My next

bubble was in the late 1970s, when 10% inflation, 70% tax rates and

a second bump in oil prices turned Texas into a home for the temporarily

insane. One of my oil clients decorated its headquarters with $300/yard

carpet with its logo woven into it. Another (bank) client changed its

name from something about farmers to one more appropriate for its position

as a major oil, gas, farmland and commercial property lender. It built

a new headquarters building, filled it with oriental carpets and hand-carved

doors, and put its trading operation in the lobby, so customers could

watch it make money. That bank is gone.

I remember

a dinner in the Petroleum Club, where one of my dining companions told

me he was cornering the market for silver. That didn't work either.

In Kuwait

in 1982 I helped the finance minister sort through the wreckage of the

collapsed souk al manakh stock market, which traded the stock of imaginary

companies, with no capital, no employees and no products, and settled

the trades with post-dated checks. Now that's a market. I saw $80 billion

of bad checks piled on one long table.

I remember

buying a cup of coffee in Buenos Aires with a 1,000,000-peso bill at

a time when bankers were lending to Argentina at three-quarters over

LIBOR because countries never defaulted on their loans. I was in Tokyo

in the late 1980s when the Nikkei was 42,000 and land was priceless,

just like in the commercial.

And I

lived through the Internet bubble like everybody else.

I wish

I could report that I remained rational during those bubbles, but, like

Mark Twain during the silver rush, I didn't. Looking back, however,

all the bubbles were situations where market dynamics had pushed prices

far away from their underlying values. Eventually they all collapsed.

Today it's important to remember that bubbles work in both directions.

Downward bubbles, where market dynamics have pushed prices far below

underlying value, collapse too. We may be in one right now.

Future

Estimates

Underlying value, or intrinsic value, is the fair value of the future

cash flow stream embodied in a security. Since we have a zero-coupon

bond market that gives us prices for future-dated cash, we should be

able to estimate the intrinsic value of any security for which we have

a reasonable estimate of cash flows.

The same

arithmetic works for any investment. First, estimate the stream of future

cash flow. Next, value each cash flow coupon, allowing for risk. Then,

add them up and subtract obligations. This is how investments are valued

in the bond and mortgage markets, in real estate markets and in private

equity markets. It's how they should be valued in the public equity

markets, too.

No multiple

of any current-year number -- not earnings, not cash flow, not book

value, not sales -- is an adequate replacement for this work. You have

to do the work.

My colleagues

and I at Rutledge Research have been using a computer-based system we

call the Value Tracker to estimate the intrinsic value of public equities

for the past 10 years. We estimate the company's future cash flow the

same way a private equity buyer would do so.

We create historical distributions for each of the business parameters

(we call them value drivers), such as sales growth, gross margin, selling,

general and administrative expenses, capital turnover and cost of capital,

that an analyst would need to know to build a business plan for the

company. We use these distributions, along with other work, to build

a complete set of financial statements -- a profit and loss statement,

a balance sheet and cash flow -- for each year for 30 years into the

future.

Intrinsic

value is the present value of the future free cash flow "coupons,"

plus the terminal value of the business minus the value of debt, preferred

stock and all other claims, divided by outstanding shares. This approach

works equally well for an industry, a sector or any other index of securities.

One of

the benefits of this approach is that it lets you use all the analytical

tricks in the fixed-income investor's bag. That's because the only real

differences between a stock and a bond are that a stock has no maturity

date and that the free cash flow coupons of the stock grow over time

(at least we hope they do). Both factors combine to make the value of

a stock many times more sensitive than a bond to changes in real interest

rates because it has a higher duration. Stocks are simply unfixed-income

securities.

This

suggests that we should evaluate the risk of equities the same way we

do in bond, real estate or private equity. Intrinsic risk is the risk

that something will go wrong with the ability of the business to produce

cash flow while you own it. Intrinsic risk, not volatility, is the risk

that can kill you. I'll be writing a lot more about this in future columns.

Market

Value

One conclusion of the work is that a company that never makes a profit

will never be worth more than the scrap value of its assets. I know

what you're thinking: Where was I in 2000 when you could have used the

idea? Fact is, in 2000 this system showed the S&P 500 to be about

50% overvalued.

What's

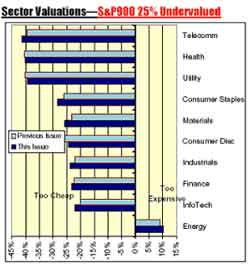

it saying now? It says the market is 25% too cheap, with substantial

differences among the sectors, as you can see in the chart below.

Source: Rutledge Research

This doesn't mean the market will go up tomorrow, or

even next week or next month. It does mean that it's 25% cheaper to

buy future income in the equity market than in the bond market. Over

the past 10 years, whenever the market gets this far from intrinsic

value, it finds its way home. When it does, the snails who buy cautiously

at current prices will make a lot of money.

|