Summary: In spite of what the textbooks say, interest rates and bond prices are not related. They are exactly the same thing. Both are identical measures the price of future money. Because of this, the principal impact of Fed policy is on asset prices and net worth, not on GDP. Failure to recognize this has contributed to the widening inequality issue that has made political differences so divisive today.

Note: Those of you who make your living in the financial markets will know all of this so you may want to go and pet your dog instead of reading it. Others may not. I have found the language of interest rates to be very sloppy in both academic and policy circles.This is an attempt to clean up a little bit of the mess.

Interest rates are, perhaps, the most important concept in macroeconomics and finance. Unfortunately, many students get their degrees without knowing just what an interest rate is. That’s why the first thing I do on the first day of my macroeconomics class is to show the students the following graphs.

A bond is just a fancy name for an IOU. The piece of paper pictured above is a bond–an IOU written by Uncle Sam promising that the US Treasury Dept. will pay the owner $100 at a certain date in the future. The one pictured is for $100 but for our illustrations we are going to pretend the IOU is for $1.00 and that date the IOU comes due–its maturity date–is one year from the date it was created, which we assume to be today. Whether it was written by Uncle Sam, by a corporation, or by your cousin Wally, a bond is still an IOU.

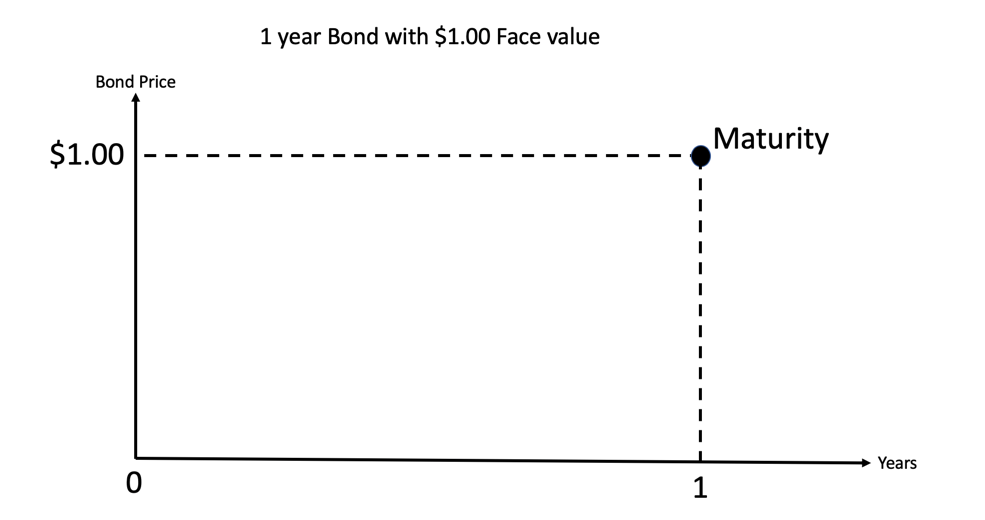

The graph above tells you that you only know one thing about the IOU, that it it is a promise to pay you $1.00 in exactly one year.

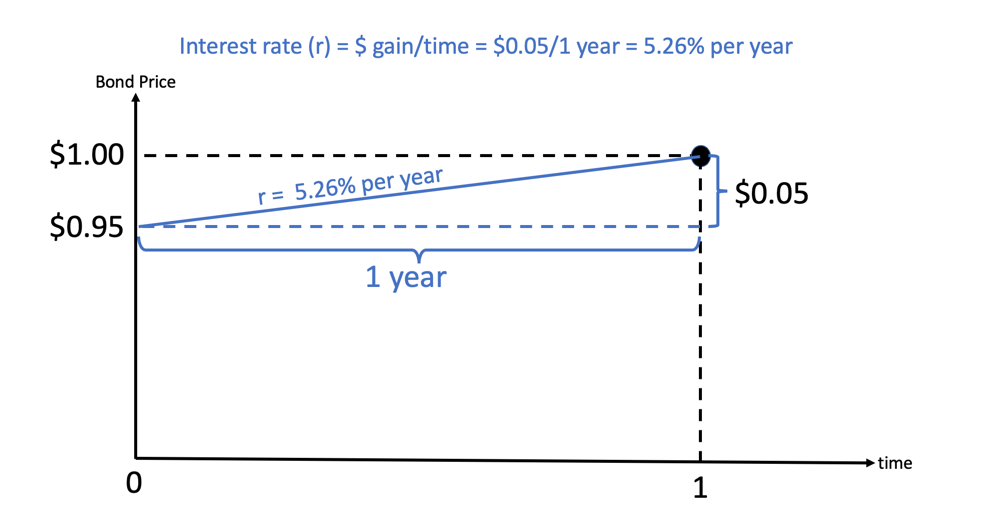

The bond price tells you how much is the IOU worth today. In most situations it wouldn’t be a good idea to pay Uncle Sam $1.00 for the IOU because then he wold get the use and availability of your money for a year for free. So, let’s say that, in order two entice you and others to buy the IOU’s Uncle Sam was only able to sell them for $0.95 for each promised dollar. As you can see in the graphic above, if you pay $0.95 today and Uncle Sam pays you $1.00 in one year, you will have made a profit (return) of $0.05 for each $0.95 you paid. The interest rate is nothing more than a short-hand for describing that situation. In this case, your $0.05 profit is 5.26% of the $0.95 you paid, i.e., the interest rate is 5.26%.

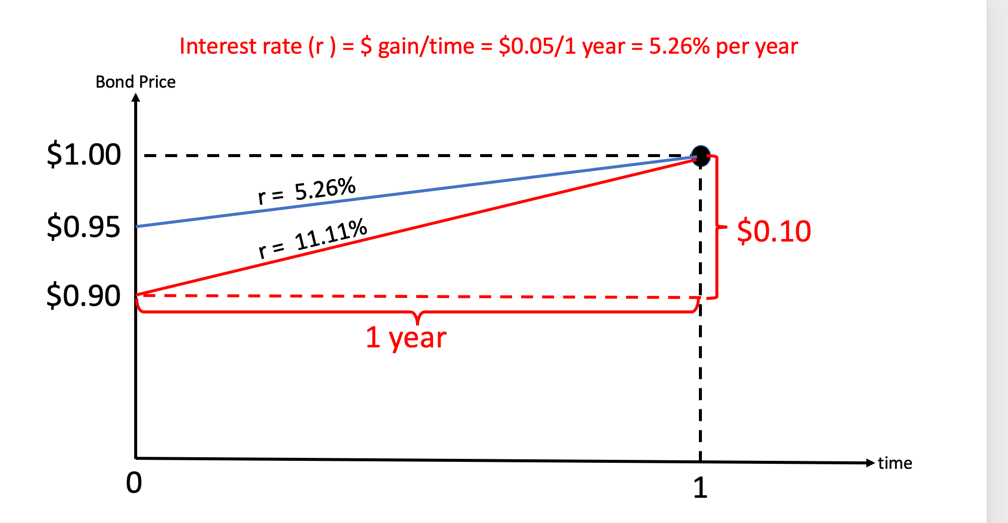

Let’s say that one New York Minute after you paid $0.95 for your IOU you learn that the going price for IOUs is now $0.90, i.e., the interest rate has increased to 11.11%. Bummer, right? This could have happened for a number of reasons. The Treasury might have sold more IOU’s than people had thought they would; someone else (the Fed? The Chinese government?) might have sold a truckload of them. Or people could have just decided they want to spend their money now, rather than a year from now because they learned that a giant comet was going to strike the earth 11 month from now. Whatever the cause it’s not good for you. Sure, you can still sell it back to the Treasury in one year (except for the comet thing). But every day between now and then, the price you could sell it for is now less than it would have been if interest rates had stayed at 5.26%.

The point of this is very simple. Whether you express it as the price of the IOU or the interest rate on the IOU, there is only one piece of information to be had. The sloppy language of the textbooks and policy papers suggest that the Fed changes the interest rate, which then influences bond prices through some causal mechanism is misleading. The bond price is the interest rate and vice versa.

To a first approximation, the only tool the Fed, or any other central bank has, is thesis of its balance sheet, i.e., how many bonds they own. That means that, to a first approximation, the only thing the Fed controls is the prices of a certain collection of assets. When they buy, say, $1 trillion worth of bonds, the direct impact is to raise the price of the particular types of securities they buy, whether Treasury bonds, mortgages or, in the case of Japan public equities.

You can equally describe this as a fall in interest rates on those securities, both absolute and relative to the prices/yields on other assets. The relative decline in yields will induce investors to sell some of them in favor of other, higher-yielding close substitutes. In this way, the direct impact on yields of Fed purchases–we call it Quantitative Easing today–will disperse across the asset markets, like ripples on a pond.

But what about GDP, the economy, incomes, output, and employment? About two-thirds of GDP is made up off services. The ripples on a pond story isn’t as convincing with haircuts or guitar lessons as it is with bonds, mortgages, stocks, and even houses. This makes Fed policy a blunt instrument for controlling GDP. Unfortunately, that is not the view of the policy crowd or the Fed staff who think they can produce GDP by buying bonds.

The upshot of this misunderstanding is to worsen the inequality issue that has torn the political system apart. It is not the difference between high-income and low-income workers that is the problem. It is the difference between the paths of the net worth economy, the people whose economic welfare depends on asset prices, and the paycheck economy, the people whose welfare depends on weekly paychecks. The recent shift of Fed policy toward ease will keep those trends in place for a long time.

I will write a separate piece digging into the investment implications of continued divergence between the net worth economy and the paycheck economy. The high-level implications are easy: businesses that make their money delivering products and services to people, industries, and geographies in the net worth economy will grow faster than their counterparts in the paycheck economy. The implied continued widening of the gap between living standards suggests that the political environment is likely to get even more unstable. I will write more on this in the coming days.

JR