NOTE: I am closing this article on Sunday night 3/15. By the time you read it I expect that markets will be even more chaotic than we have seen to date. A few hours ago the Fed announced a joint operation (Fed, ECB, BOE, BOJ, BOE, BOC, SNB–apologies to any omitted) to push US rates near zero and inject a historically unprecedented tsunami of liquidity into global financial markets. The broad US stock market futures immediately went down limit (5%); European and Asian markets fell sharply (3-5% at the time of this writing) too. And worst of all, I am quarantined in my house along with all other Californians over 65.

As I said on CNBC Friday afternoon, I believe we have now crossed the dividing line between macroeconomic problems and a financial crisis. That dividing line is the moment financial markets switch from normal lending to non-price credit rationing, which makes it difficult for small, private companies to get working capital. The result will be a sharp but temporary recession that will not improve until it is clear the coronavirus has done its worst and people feel safe working together again.

As one old enough to be quarantined, I have lived through a number of pandemics and other crises. This one will end too. When it does, the global economies will spring back to life and cautious investors who can remain calm will feast on a market where the best companies in the world are selling at extreme discounts. Everything we do at Safanad is to be ready for a time like this. I have written the article below to give you my thoughts about how, as investors, we can all find our way through this difficult environment. I hope it is of help to you. JR

Investors are justifiable frightened today. In a New York Minute*, we have gone from the longest recovery and greatest bull market in history to wildly gyrating stock prices, a collapse of the global oil market, and the brink of recession. In times like these, our most difficult job is to control ourselves. Our brains know that we should calm down, think, and take careful action. But our fight or flight response screams for dramatic action. Here are a few things I find it helpful to do to preserve health and wealth in these situations. (*The definition of a New York Minute is how long it takes from the moment the stop light in front of you turns green and the taxi behind you honks his horn.)

I chose the title of this article, with apologies to Gabriel García Márquez, for the same reasons he did, to highlight the parallels between physical diseases, like cholera and coronavirus, and afflictions of passion and fear, cólera, or heat, in Spanish. The coronavirus is what is keeping people off the airplanes, cruise ships, and hotels. The cólera is what is making investors bail out of the stock market and consumers empty the shelves in the supermarkets.

Photo below taken over the weekend by a friend in a London food market.

I teach Behavioral Finance to PhD students. So, in principle, I should be immune to all of the biases and mistakes that have been catalogued by the Kahnemans and Tverskys over the past 40 years. But I freak out just as much as anyone else when I see stock prices swing 1000 points in an hour, as they did today. And I have plenty of rice, pasta, soup and, most importantly, cabernet in my garage.

At my advanced age, I have learned several tricks that I use to manage myself in these situations. I have given them behavioral finance names to make them sound more official.

- The Armageddon Bias.

- The Briefcase Rule

- The Fireside Theater Effect

Armageddon Bias is what is freaking people out now. Faced with sudden, life-threatening risks, people have a tendency to think that Armageddon is near and the world is ending. As I reminded the anchors on CNBC last week, the world can be difficult but it rarely ends. But that doesn’t stop people from heading for the exits when they think the theater is on fire.

The dimmest bulb on the planet knows that yelling fire in a crowded theater will cause a stampede. Unfortunately, economists haven’t figured that out yet. One of the three glaring deficiencies in modern macroeconomics is its dependence on representative agent models that every person in an economy is a clone of all the others, that they behave in exactly the same way, and that nobody talks to each other, i.e., the behavior of any one person is independent of the behavior of everyone else.

In the real world, of course, people’s behavior is highly interdependent, especially when they are frightened. That’s why we see stampedes in crowded theaters, flash mobs, runs on banks, stock market crashes and, for whatever reason, toilet paper hoarding (Charmin Syndrome?). Interestingly, these human events share the same underlying mathematics with all of the sudden, violent events in nature, including avalanches, tsunamis, earthquakes, tornadoes, and hurricanes, all known as phase transitions. And, like in nature, these sudden violent human and social events are all temporary. This one will prove temporary too.

The Briefcase Rule is a circuit breaker tactic that has saved me a lot of money in my life but it cost me a lot of money to learn it. One early morning in January 1981 in New York, as I walked from my hotel on 59th St. to the CBS building on W. 57th St. to do my first-ever interview on CBS Morning News, I was scared to death. On the way there I passed a shop with the fanciest briefcase I had ever seen in the window, the kind of briefcase a really famous and powerful person might carry. Too bad the store wasn’t open yet.

At CBS, I had breakfast with Dan Rather and his whole production team and had an extended and somewhat combative interview with Dan, Diane Sawyer, and Jane Bryant Quinn about how the Reagan Economic Plan would impact the economy and financial markets. I said there would be a sharp drop in inflation and drop in marginal tax rates that would push interest rates sharply lower and stock prices up, and have massive implications for US businesses and investors, the topic of Op-Eds I had recently published in the Wall Street Journal and New York Times. Jane pushed back that inflation would never fall so none of that would happen.

Anyway, as my mom used to say, the interview was very upsetting and on the walk back to my hotel I felt a deep and intense need to bolster my shattered ego. So, when I passed the shop with the fancy briefcase, I went in and paid $400 I didn’t have for a briefcase that I didn’t need because a guy who went on CBS Morning News surely deserved it, right? It was beautiful, for sure, but only two inches deep and entirely useless. I took it back to my office, put it on the shelf above my desk where I couldn’t help but see it, and left it there for more than a decade to remind myself every day not to do such stupid things. After that, whenever my insecurities screamed at me to do a repeat, I invoked the Briefcase Rule, and simply told myself that I would buy it–tomorrow–after I had calmed down.

As stock prices crashed over the past week, my brain told me that it was too soon to buy stocks, because prices would surely fall further as the coronavirus numbers grew. But my body told me to buy them now before their prices went back up. So, I invoked a variant of the Briefcase Rule and bought a tiny amount of the stock that I felt was the most oversold and told myself I might buy more tomorrow. As a result, I am still sitting on a pile of cash waiting for the day when my brain says it’s OK to proceed. You can do the same thing–just pick an amount that is so small relative to your investment portfolio that it doesn’t matter, even if it is one share.

The Fireside Theater Effect.

The upshot of all this is that they were right on Fireside Theater when, at the beginning of every show, the announcer reminded us that “We are all Bozos on this bus.” For investors, controlling our emotions or, failing that, severing the link between our emotions and our actions, is half the battle. The other half is to use our brains to understand what is happening and devise strategies that make sense for current conditions. I will turn to that now.

The Situation

Make no mistake–the situation is very difficult. Let’s list a few of the factors that are making things so scary today.

- Complacency. The economy has been growing, jobs increasing, interest rates falling, and stock prices rising for so long that people have forgotten that it can be any other way. The financial markets are now almost totally populated with people whose careers began after 1981. That’s what has made people blithely chase valuations to levels we have never seen and left the financial system poised for trouble.

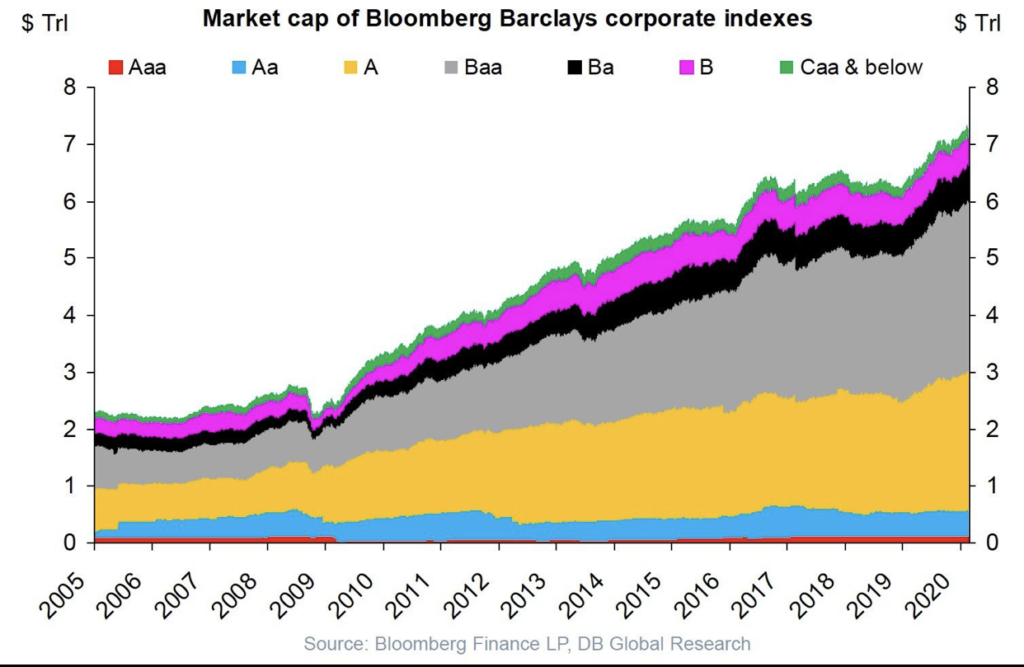

- Junk. While households have significantly reduced debt since 2008, corporations and governments have taken advantage of low interest rates by gorging themselves on debt. Corporate debt has more than doubled since the last financial crisis, much of it used to buy back stock. As you can see in the chart, below, almost half of it, some $3 trillion, is rated by Moody’s Baa, the lowest Investment Grade (IG) rating, one step above junk. Much of this near-junk is owned by mutual funds with strict language in their prospectuses that forces the managers to hold the bulk of their assets in Investment Grade bonds. Meaningful reduction in cash flow for these companies means they run the risk of losing their IG ratings, which would force mutual funds to sell them. This is the reason junk bond spreads have spiked in recent days as investors worry about the coronavirus tipping the US into recession.

- Trade War Damage. The extended global trade war, along with Brexit and other political uncertainties have slowed capital spending and interfered with the flow of parts and components along global supply chains, reducing GDP growth everywhere.

- Supply Chain Blockage. The early days of the coronavirus epidemic in China shut down much of China’s industrial activity, both slowing the flow of parts and components for industrial companies in other countries and reducing demand for oil and other commodities in global markets.

- Oil Price Collapse. Most recently, the drop in oil prices has led to a fallout among major oil producers, with both Russia and Saudi Arabia increasing production and reducing prices. leading to a collapse of oil, gas, and coal prices. Many of the near-junk bonds discussed above were issued by highly-levered US shale oil producers, making them, and the mutual funds that own their shares, particularly vulnerable to declining revenues caused by falling oil prices.

- Divisive Politics, Damaged Institutions. A deeply divisive election season that will leave investors unable to predict tax rates a year ahead and further delay capital spending decisions.

Together, these factors are sufficient to produce a significant slowdown in growth or a mild recession in 2020. But they do not constitute a full-blown financial crisis. The difference between a slowdown and a financial crisis is whether financial markets are still open for business, using price to allocate credit, or have switched to non-price credit rationing like we saw in 2008. I believe we may have crossed that line late last week when major borrowers began drawing down their credit lines. As we know from the last financial crisis, it is a very difficult time for businesses and investors. It is also a time when some investments do better than others. Let’s focus on those.

Not All Sectors Are Created Equal

Some parts of the economy are caught in the cross-hairs of the current financial crisis. Others are less negatively affected, and some actually derive advantage from the situation.

Among the most disadvantaged sectors, some are obvious are:

- Energy and commodity producers.

- Heavily indebted companies.

- Companies that are heavily dependent on foreign trade for their revenues.

- Companies that specifically earn their revenues from travel and group events, including airlines, shipping companies, hotels, and sporting events.

Among the sectors that are either somewhat protected from the current disruption or benefit from it are:

- Companies that benefit from the relentless growth in computational power and the flow of data due to 5G telecom networks, Cloud services, autonomous vehicles, and the collection of products referred to as the Internet of Things.

- Companies that allow people to pursue their careers regardless of trade wars and epidemics, including remote work and online education. That includes videoconferencing companies like Zoom, remote work services, and logistics companies that transport bring the goods people need directly to their door, and education companies with the capability to teach students online.

- Less leveraged companies that produce strong free cash flow, giving investors a source of current income as an alternative to low-yielding bonds and other fixed-income instruments. These are the companies that will be able to launch powerful stock buyback programs at discount prices, shrinking their market float and pushing prices higher.

- Companies that provide mission critical services demanded by irreversible demographic change, such as the aging of the Baby Boomers and Millennials forming families and becoming homeowners, just as their parents did.

- Healthcare companies that can meet the growing need for health, medical, and wellness services for aging Baby Boomers (me). This includes fast-growing home-care and tele-medicine businesses and communications providers that keep families connected.

Conclusion for Investors

As I have consistently advised for many months, in this situation investors should be cautious, not aggressive, holding abnormally large amounts of cash. Cash also lets you pick off the shares of world-class companies at a discount when investors freak out over headlines.

For private companies and private equity investors, the risks are a little different. Their objective is to make sure that temporary air pockets in the economy and credit markets don’t cause the company irreparable damage by breeching debt covenants and shutting down the company’s access to working capital, leaving the company unable to refinance short-term debt during a temporary credit squeeze. That means being less aggressive in bidding for deals, more cautious on exit multiple assumptions when underwriting deals, taking less leverage than banks offer, and choosing longer maturities and fixed rates when you borrow.

For real estate investors, the same advice applies with one additional wrinkle. Once upon a time inflation was 10-15% per year) and it was standard practice to index rents by tying them to the CPI or some other measure of inflation. Today, inflation has been 2% for so long that almost every real estate deal I see specifies that rents will rise by 2% per year, or 10% every 5 years over the entire term of the lease, which, including options, means 15 or 20 years into the future. Given the likelihood that the Fed and other central banks will continue to respond to financial crisis like they did today by buying bonds and printing money, I would much rather have the protection of indexed rents than the promise of a 2% increase.

JR