Summary: China grew at a 6.2% annual rate in Q2/19. With a single exception (The Financial Times), every financial news source I checked covered the story by running alarming and misleading headlines. Journalists–you can do better than this.

A sampling of headlines from major sources of financial news talk about the GDP number as “27 year low”, “weakest pace in 3 decades”, “hammered by tariffs”, “trade war stings”, and the winner of the soap opera prize, “…its economy probably can’t go on like this.” (Swoon!) These headlines may catch eyeballs and sell advertising but they are grossly misleading for investors.

Bunk. This is the story journalists should have written.

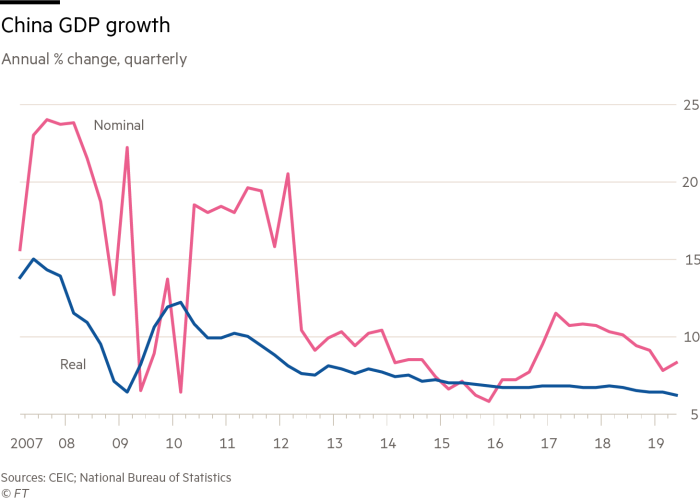

This morning, China reported 6.2% GDP growth for Q2/19, as shown by the blue line in the chart below from the Financial Times. That’s in line with analyst expectations, lower than the 6.4% reported for Q1/19, and consistent with the gradual cooling of China’s growth over the past seven years. Nominal GDP (the red line in the chart), a good proxy for average income growth in urban areas, grew at just over 8% per year.

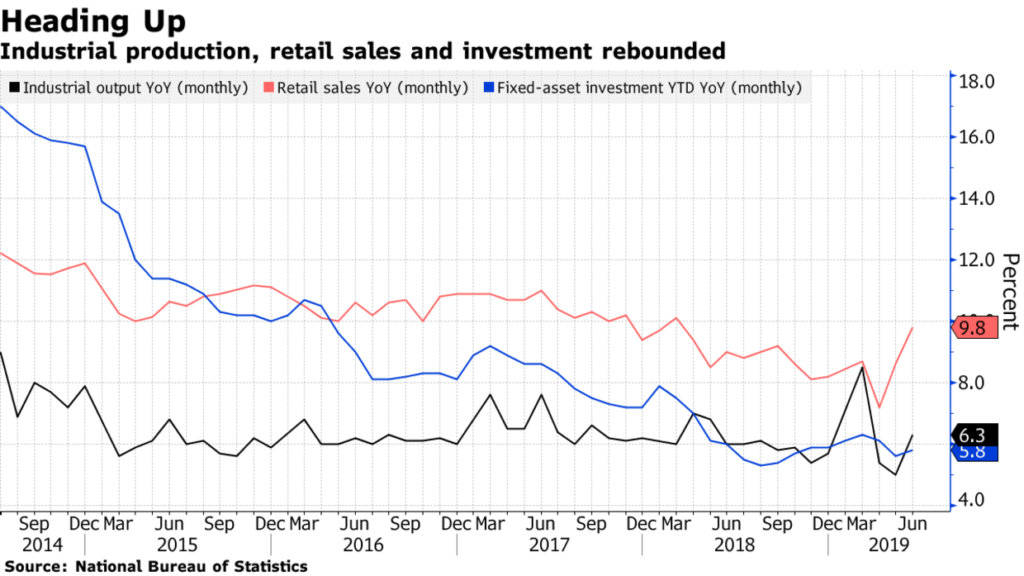

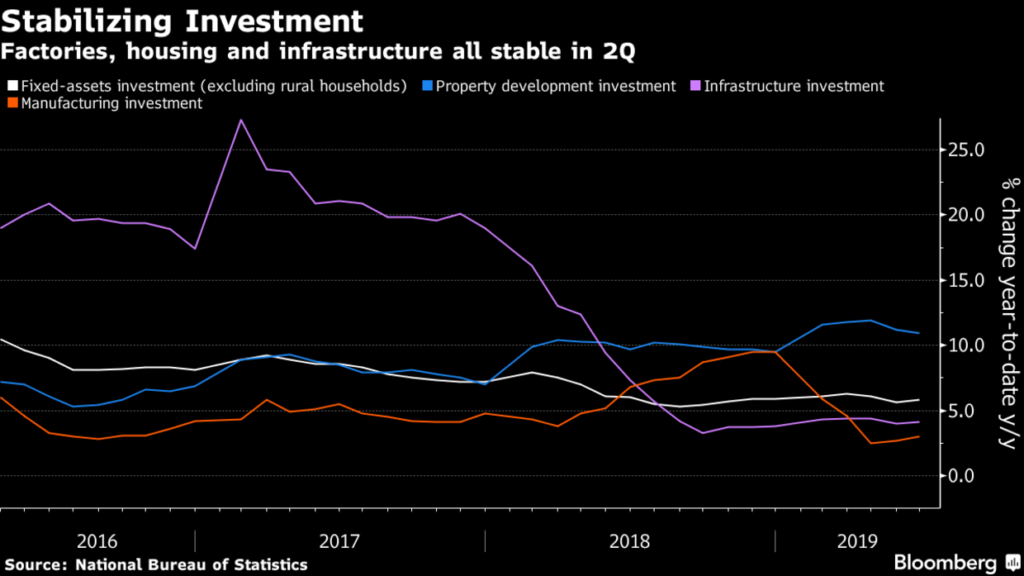

Retail sales grew 9.8% in June, up from 8.6% in May, driven by robust auto sales (17.2%) and strong sales of furniture and household appliances. Industrial production grew 6.3% in June, up from 5.0% in May. Investment in fixed assets, property development, infrastructure and manufacturing firmed, as shown in the second chart below from Bloomberg.

The weakest sector was traded goods. Exports declined by 1.2% in June (-2% expected); imports were down 7.3% (-4.5% expected). Exports to the US were down 7.8% in June (the first full month of increased tariffs on both sides); imports from the US were down much more sharply (-31.4%).

These trade numbers, of course, don’t fit the rhetoric that the trade war has brought China to its knees. Chinese imports are actually down a lot more than its exports, even though Chinese incomes are still rising. There is a simple reason for that. The RMB is down by about 10% against the dollar since the trade war began. For US consumers, a 10% tariff imposed on some Chinese goods was roughly offset by the 10% drop in the RMB so the price of Chinese goods in dollars was unchanged. (Chinese goods not impacted by US tariffs are actually cheaper today, in dollars, that before the trade war.) That’s why China’s exports to the US have not fallen much. But for Chinese consumers a 10% tariff on US goods and a 10% increase in the price of the dollar (drop in the RMB), together, increase the prices of US goods exported to China by roughly 20%. That’s why Chinese imports have fallen so much.

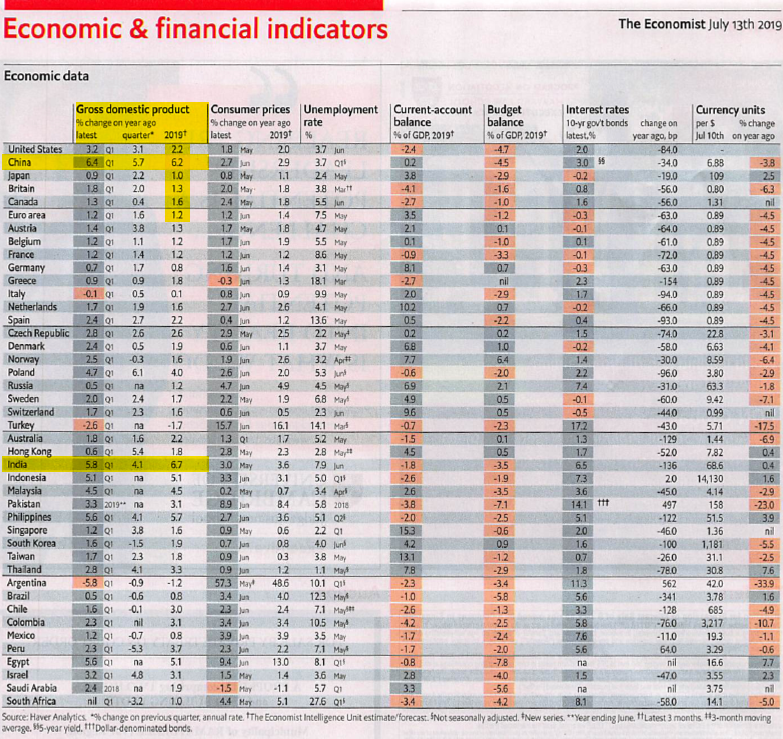

The bottom line is that China’s growth was not great but better than a sharp stick in the eye. Real growth of 6.2% is still a huge number–3x US, 5x EU, and 6x Japan growth rates–as you can see in the chart below from this week’s The Economist.

Trade hawks in the White House will argue that China has been cheating by devaluing its currency. But the fact is, the RMB was pushed down by global investors pulling their capital out of China due to the trade war. The PBOC, for its part, was trying to hold the RMB up, not push it down.

The trade war has caused damage to China’s economy, of course, just like it has in many other places. Most notably, companies are working hard to reconfigure their supply chains to avoid shipping products directly from China to the US. I say directly, because trade statistics count the full value of an item (like an iPhone) shipped from China to the US as a Chinese export, even though most of its value may have been produced in the US, Korea, or Taiwan. If they ship the iPhone to Timbuktu and paint it brown there, the whole value of the export will now show up as a Timbuktu export to the US with the resulting trade surplus. Of course, fundamental supply chain changes are taking place too as companies move assembly operations from China to Vietnam, Cambodia or some other more favored location.These supply chain changes don’t happen overnight, but they will go on for a long time.

China does have growth problems; they are caused by the inability of its banking system to provide capital to small, private companies and by its heavy debt burden. The shutdown of the shadow banking sector last year has wiped out most bank lending to small, private companies, known in China as SME’s. In May, regulators seized Baoshang Bank, which sent shock waves through the interbank loan sector. The government has thrown everything they have at the problem, including massive liquidity injections by the PBOC and heavy-handed mandates to brokerage firms to lend money to small banks. But the SME capital shortage is structural; it won’t go away. And then there is the debt problem. That won’t go away either.

Given these problems, today’s GDP report was actually surprisingly good. Of course, no country can grow at 7, or 6, or even 5% forever. To a first approximation, we should expect growth rates to decline every quarter for the next couple of decades as Chinese living standards approach developed country levels.

Scary headlines attract readers; readers attract advertising dollars. That means every quarter you will see headlines that China’s growth is the slowest since 1992. Just don’t confuse the headlines with the facts.

JR