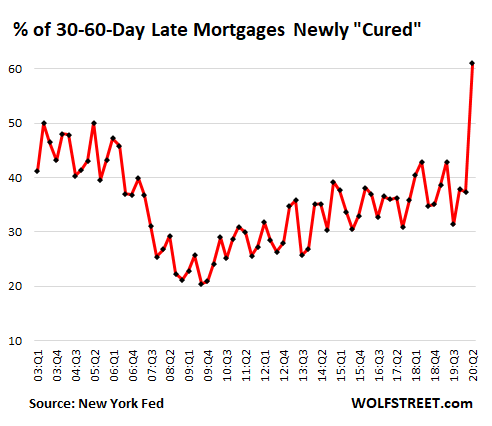

We need to be careful how we read the government reports, especially during unusual times. The CARES Act granted forbearances on federally backed mortgages that prevent foreclosures and evictions, keeps lenders from reporting missed payments to borrowers’ credit files, and magically “cures” delinquent mortgages on lenders books. As a result, 61% of delinquent mortgages were anointed as “Cured,” as shown in the chart below based on data from the New York Fed Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit. If you are a fiction lover, I strongly recommend that you read it, especially the footnotes.

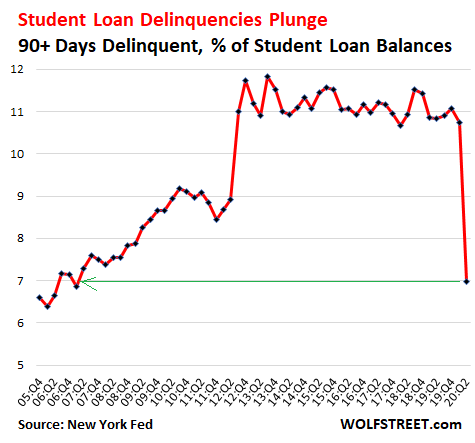

Student loan delinquencies also magically disappeared when the Department of Education made the “decision” to report all loans eligible for CARES Act forbearances as current, allowing banks to report unpaid loans as if they were being paid. In effect, the CARES Act has placed a (temporary?) moratorium on GAAP accounting too.

So, why does this matter? Because, while many people took advantage of the various forbearances and moratoria and did not make payments on their mortgages, student loans, auto loans and credit cards, those missed payments did not show up in their credit reports. They also don’t show up in the statements analysts rely on to make judgments about the quality of lenders’ loan books or in the Q2 earnings reports. Unfortunately, just like deferred taxes and most PPP loans, the missed payments and interest costs are going to have to be paid whenever the forbearances and moratoria end, as they surely will. At that point they are going to show up big time.

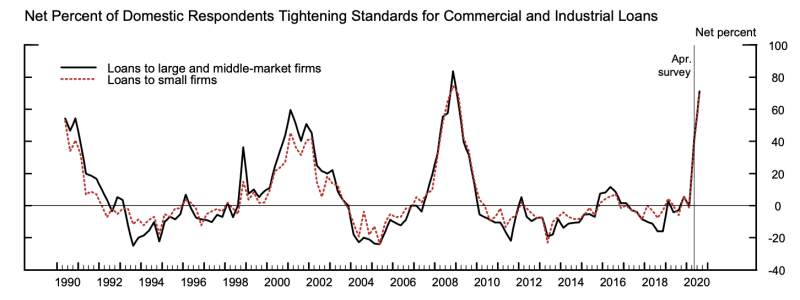

These extraordinary actions actions have delayed, but not prevented, the credit crisis that failed to happen in March. Lenders, of course, who are no longer burdened with opening all the envelopes with mortgage payments inside, are fully aware of the truth beneath the numbers. They have already started to tighten lending standards, as shown in the chart below for commercial and industrial loans from the Federal Reserve Board’s July 2020 Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey.

Which brings us to the credit crunch. Credit crises are not caused by high interest rates. They occur when credit markets experience a sudden cascading network failure and lenders stop allocating credit based on risk-adjusted returns. In the ensuing non-price credit rationing episodes, small and medium size businesses lose access to working capital from traditional sources and are forced to seek working capital from alternative providers at much higher cost. Output declines sharply, so central banks push “headline” rates (Tbills, Fed funds) even lower. Business owners are confronted by the irony of seeing low interest rates in the newspaper while having to pay equity returns for collateralized senior debt in private markets.

Formally, such cascading network failures represent “phase transitions” from a general equilibrium state, where credit is allocated by price, to a much less efficient far-from-equilibrium state where credit is allocated by non-price rationing. For reasons having to do with differing network architectures, cascading network failures are much more likely to happen in financial markets than in markets for goods and services, which is why owe have repeated credit crises rather than potato crises or iPad crises. Like other phase transitions in nature, credit crises are sudden, violent, and (thankfully) temporary. Credit crises are painful but they set up tremendous buying opportunities for investors with ample cash.

Conditions are ripe for this to happen late this year or early in 2021 when the forbearances and moratoria are gone and the debt is again visible. That’s when the real distressed debt opportunities will be available for investors patient enough to wait.

JR